I think a lot about the future of music and the arts. It’s my calling and my passion to help today’s musicians use their art in order to make their mark and have an impact on society in our changing landscape. It is also my job at Yale to inspire and empower our students to take their artistic training and help them find a way to live a sustainable and meaningful life.

I think a lot about the future of music and the arts. It’s my calling and my passion to help today’s musicians use their art in order to make their mark and have an impact on society in our changing landscape. It is also my job at Yale to inspire and empower our students to take their artistic training and help them find a way to live a sustainable and meaningful life.

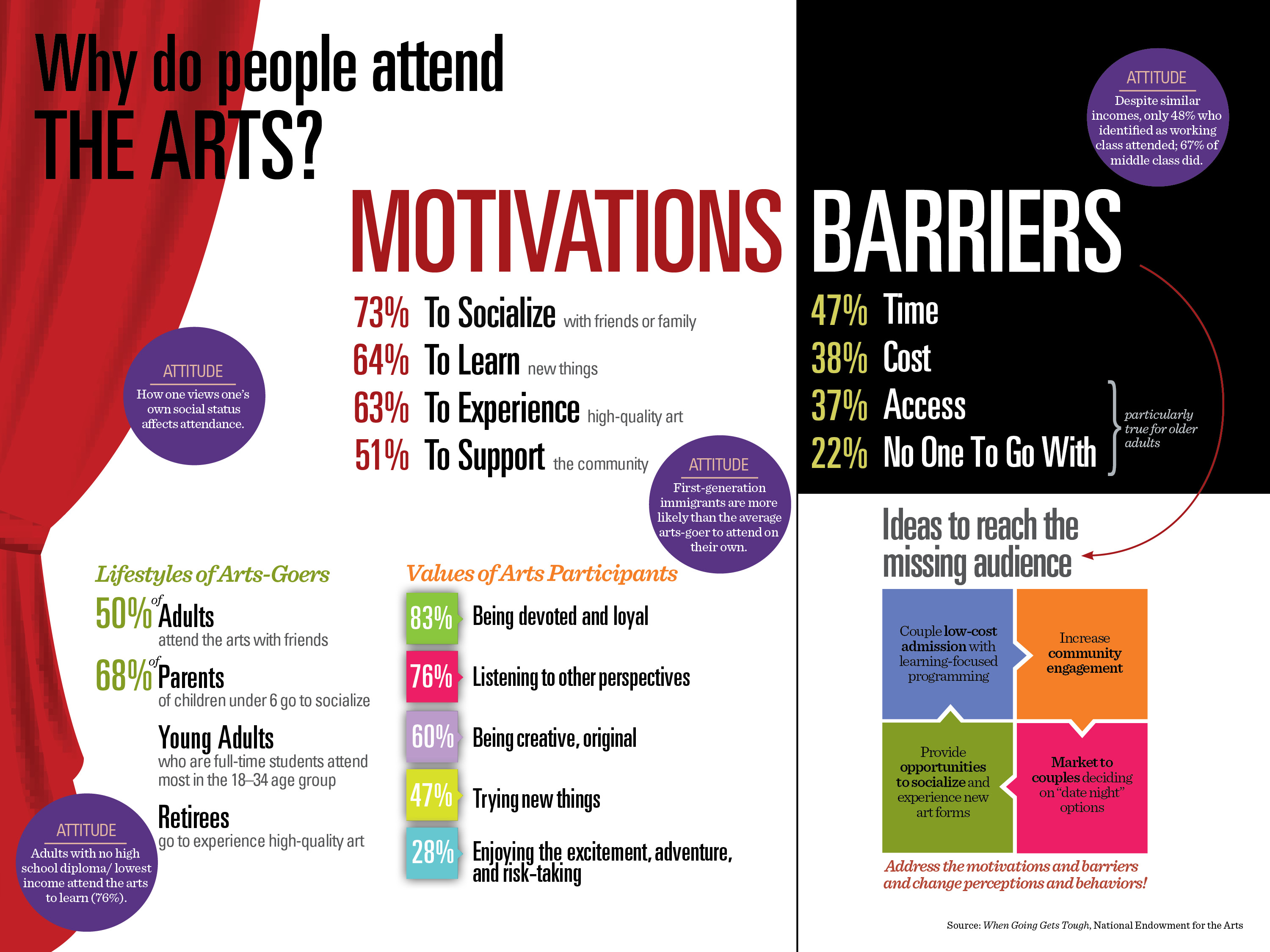

Lately, I have had an infusion of information about this very topic: the Amazon series Mozart in the Jungle, as well as the NEA’s new report on the attitudes, motivations and barriers for why people attend arts events at different stages of their lives.

Let’s start with Mozart in the Jungle, a mini-series purporting to show what really goes on backstage in a major symphony orchestra.

Based on a memoir by oboist Blair Tindell called Mozart in the Jungle: Sex, Drugs and Classical Music, the series involves a brilliant young temperamental Latino conductor, Rodrigo de Souza (loosely based on Gustavo Dudamel) who has been hired to shake up the financially-challenged New York Symphony. For those of us who work in the classical music field, many of the scenarios are exaggerated or implausible, yet the story gives us some interesting food for thought about the state of the field and what needs to be done to make classical music more relevant to today’s culture.

My favorite episode so far is The Rehearsal.

Our Maestro, who has been struggling to inspire the musicians to make great music as well as to win their respect, comes up with a novel plan: He cancels rehearsal and instead takes the orchestra on a surprise field trip to an abandoned back lot (which he has entered thanks to a pair of wire cutters).

His project? To open up the musicians and unleash their creativity.

The musicians are visibly uncomfortable with the entire setup but Rodrigo allays their fears, instructing them to go back to basics and get in touch with their environment. They begin to rehearse Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture (without music!) and the magic begins: The musicians come alive to make thrilling music, members of the community gather in amazement, people come out onto their balconies to listen and to film the performance, the neighborhood children conduct alongside Rodrigo and mingle with the musicians. I confess it brought tears to my eyes as I thought, “Now this is what I call community engagement!” The rehearsal ends as pizza and beer are delivered and we witness a block party, with food, dancing and joyous impromptu music making. There it is: music as the glue to bring people together in their natural environment.

And then reality sets in.

The police arrive to break up the unauthorized use of the space, taking Rodrigo and the musicians into custody for trespassing. The musicians are bailed out by the board chair, Gloria (who functions much more as an Executive Director than a board chair—but that’s another story!). However, this episode bonds the musicians to Rodrio and Gloria, who is deeply concerned about the Maestro’s erratic behavior, finally sees his value to the institution. While she is still nervous about his unorthodox approach, she tells him how much she values his talent and she enlists his support in helping the orchestra to dig out of its financial difficulties.

One more thing.

In the cab ride home from the police station, Gloria hands Rodgrigo a bill for $80,000 from the union representative, claiming that the rehearsal was in fact a performance—and the Maestro agrees to pay for it out of his pocket.

Let’s cut to the recently released report from the NEA based on a 2012 survey that examined the attitudes, motivations and barriers for attendance at cultural events at different life stages (e.g., parents with children, older adults, retirees.) While previous NEA studies have focused on the demographics of people who attend arts events, this report explored why Americans attend or do not attend arts events.

The survey found that people attend arts events (music, dance, theater and visual arts) for the following reasons:

- 73%: To socialize with family and friends

- 64%: To learn new things

- 63%: To experience high quality art

- 51%: To support the community

The survey also delved into the barriers that prevented people who were interested in attending a specific event but did not go.

The common barriers for 31 million adults-or 13 percent of those surveyed—were as follows:

- 47%: Lack of time, particularly for the nearly 60% of people with children under the age of 6;

- 38%: Cost

- 37%: Access, particularly for retirees, older adults, and adults with physical disabilities, estimated to total approximiately 11 million people.

- 22%: No one to go with

Look how well the rehearsal in Mozart in the Jungle responds to these factors:

It was a social activity in the community that provided a new learning experience of high quality art.

There was no problem with time, cost, access or having no one to attend because it happened spontaneously in the neighborhood, was free of charge and was filled with people who knew each other.

Yet consider the problems that exist in hosting this kind of block party under today’s models:

- How does it square with the union rules?

- How well could a symphony orchestra’s budget accommodate such an event?

- Where would the funding come from to host a neighborhood rehearsal of a major symphony orchestra?

- How many maestros would be willing to or could even afford to write a check for $80,000?

The list could go on but you see the point.

We need to rethink our institutions in order to allow for more experimentation and more meaningful, spontaneous and fun experiences with music. The young musicians whom I know question our models and are searching for a new way to present our music and make it relevant. What’s your solution?